Invest South/West in North Lawndale

December 14, 2021

An abridged version of my final analysis for 494AG: Neighborhood Analysis. All analysis and visualizations produced in R

Invest South/West Program

The Invest South/West initiative was announced Fn fall of 2019, targeting 10 neighborhoods and 12 commercial corridors, aiming to invest $1.4 billion dollars of public and private money and potentially expand the program after the initial phase (City of Chicago, 2021). According to the City’s website, the areas were chosen using two main criteria, “the existence of at least one well-developed community plan with a commercial component, and the existence of at least one active commercial area at a specific node or intersection” (City of Chicago, 2021). Described in their two-year update of the initiative, projects have focused on “mixed-use construction projects, the adaptive reuse of historic buildings, new plazas, small business grants, and related public realm improvements that restore neighborhood vitality and provide a catalytic foundation for ongoing public and private investment” and have so far invested $525 million public dollars and attracted $575 million dollars in private investment (Lightfoot, 2021).

In North Lawndale, a two-year update highlights a mini-golf course at Douglas Park and the redevelopment of 3400-3418 W. Ogden Avenue named Lawndale Redefined, sited between Homan Ave. and Central Park Ave. As the plan presently exists, it aims to add sixty mixed-income apartments, market rate townhomes, as well as retail space and a community center which will add approximately 30 jobs (Lightfoot, 2021). A pitch video shows support from various community partners and the majority Black-led development team as well as many community partners; Black Men United, the local chapter of the NAACP and more (Department of Planning and Development , 2021b). Developers and architects clarify that 48 of the of the 60 units will be affordable units, far more than current ordinance requires. The mix of retail, grocery, greenspace, and public space promises to honor the neighborhood’s history and create a lively activity center. The centerpiece of the program, The Cube, promises to invest in residents through a technological training and incubation facility (Department of Planning and Development, 2021b).

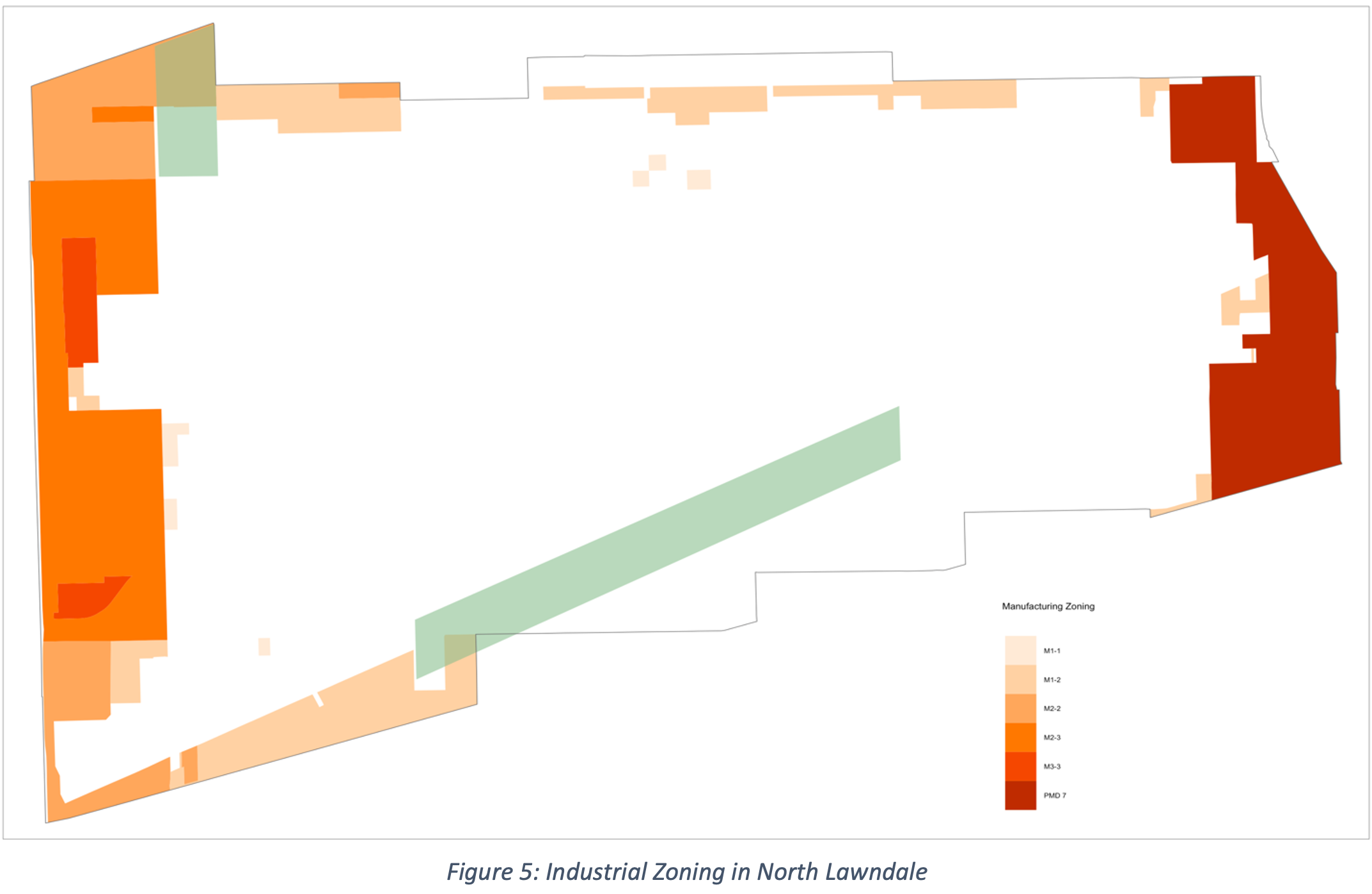

Not mentioned in the two-year update but present elsewhere on the ISW website is an open process for redeveloping 4300 W. Roosevelt Road, a 20.8 acre collection of vacant lots on the Northwest corner of the community, part of an effort to revitalize this industrial corridor. While the final use of this space is yet to be determined, per the existing proposal materials and department of Planning and Development presentation (Department of Planning and Development, 2021a), the site will most likely include some mix of mostly cold storage and last-mile distribution centers, and a small amount of square footage dedicated to an incubation space or other community development space

Travel in North Lawndale

Click Below for an interactive view of Chicago Transit Authority ridership

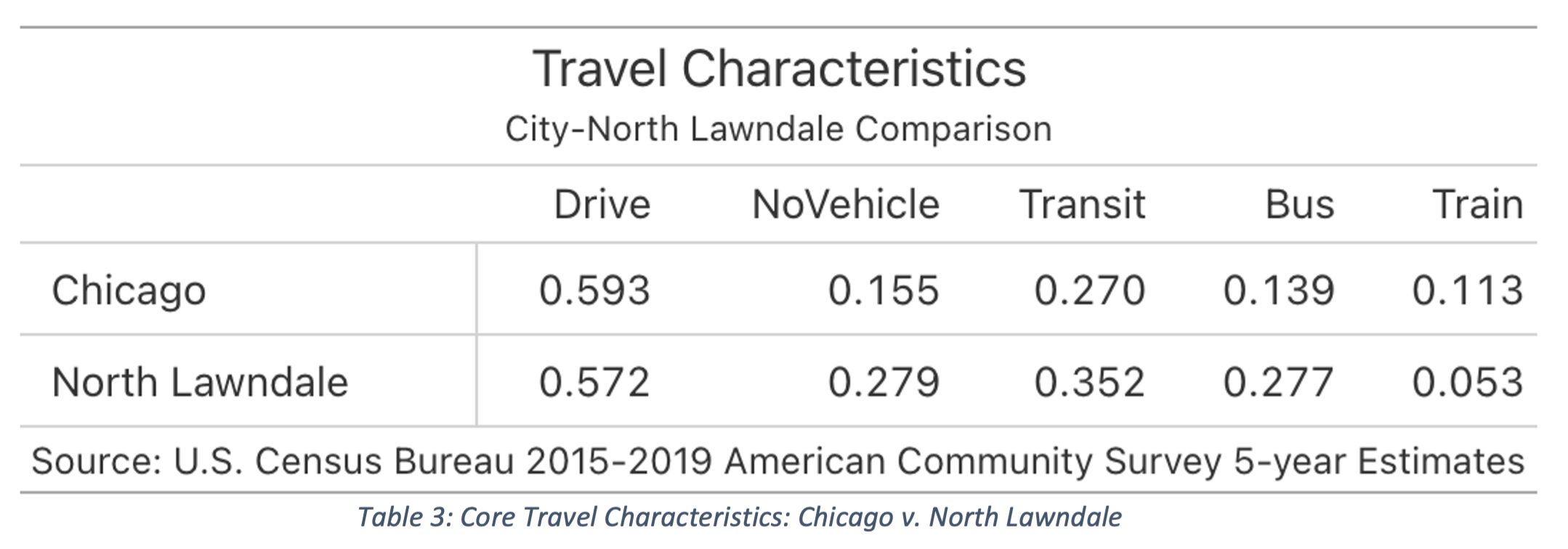

To gain some insight into who is likely to benefit from the Invest South/West developments, we can approach the issue by thinking about the relationship between income and travel mode which has been remarked as the most important determinant of travel mode by organizations such as the American Public Transportation Association (2017). Their work tells us that in general, bus transit tends to be highly used by the lowest-income workers and rail transit tends to be used by higher-income riders. In the context of a neighborhood like North Lawndale with a low- to median-income, it is important to nuance this schema and note that most users of transit in the area, regardless of travel mode, are likely captive users.

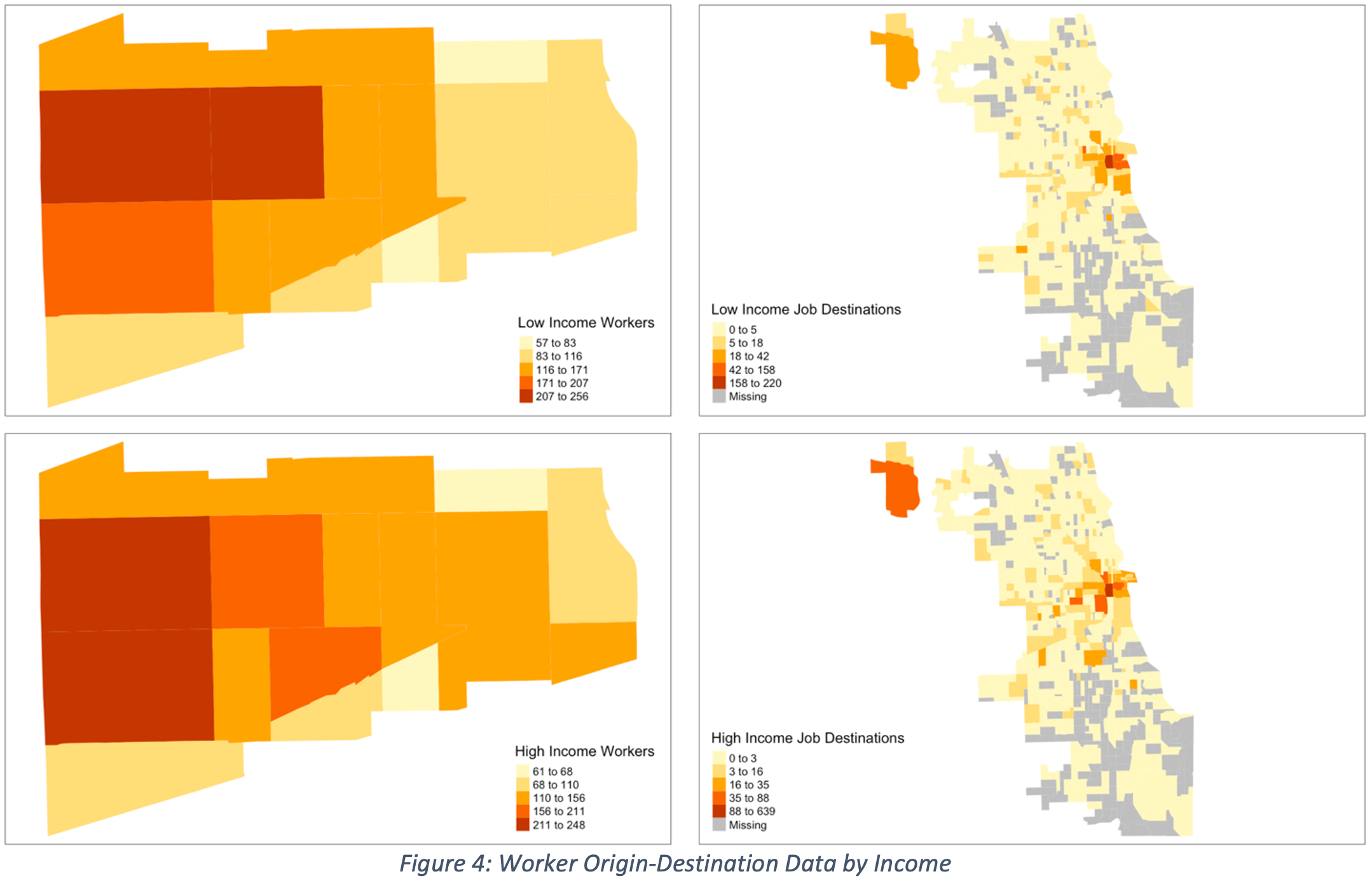

Looking at where North Lawndale residents travel for work, the case for both low-income and higher-income workers is that jobs are clustered around the loop though they diverge when we look at the number of workers who commute to places outside of the loop. In the case of low-income earners, a significant number of jobs are in census tracts outside of the loop whereas the clustering of higher-income jobs in the Loop is more dramatic.

Given the distribution of jobs we would expect to be bus to be used at high due to a high number of jobs outside the core, jobs that rail transit is not suited to serve. If we look at ACS estimates of how workers in North Lawndale commutes, we find that this is in fact the case; around 28% of North Lawndale workers utilize bus transit (twice the city rate) and only 5.3% utilize rail transit (less than half the city rate). The rail routes in the area are among the least utilized in the city while two of the bus routes that pass through the area, Pulaski Road and Central Avenue, are among the busiest on the West Side and the city more generally.

Interrogating Invest South/West

Figures 2 and 5 show ISW developments in green, the Ogden Commercial corridor, where the Lawndale Redefined project will be built, in the center and the industrial site on the top left. Its current siting, between two busy bus routes on Homan Ave. and Central Park Ave. and its short distance to the Central Park and Kedzie Pink Line Rail stations show that thought has been given to choose a site that will be accessible to a large swath of North Lawndale’s residents.

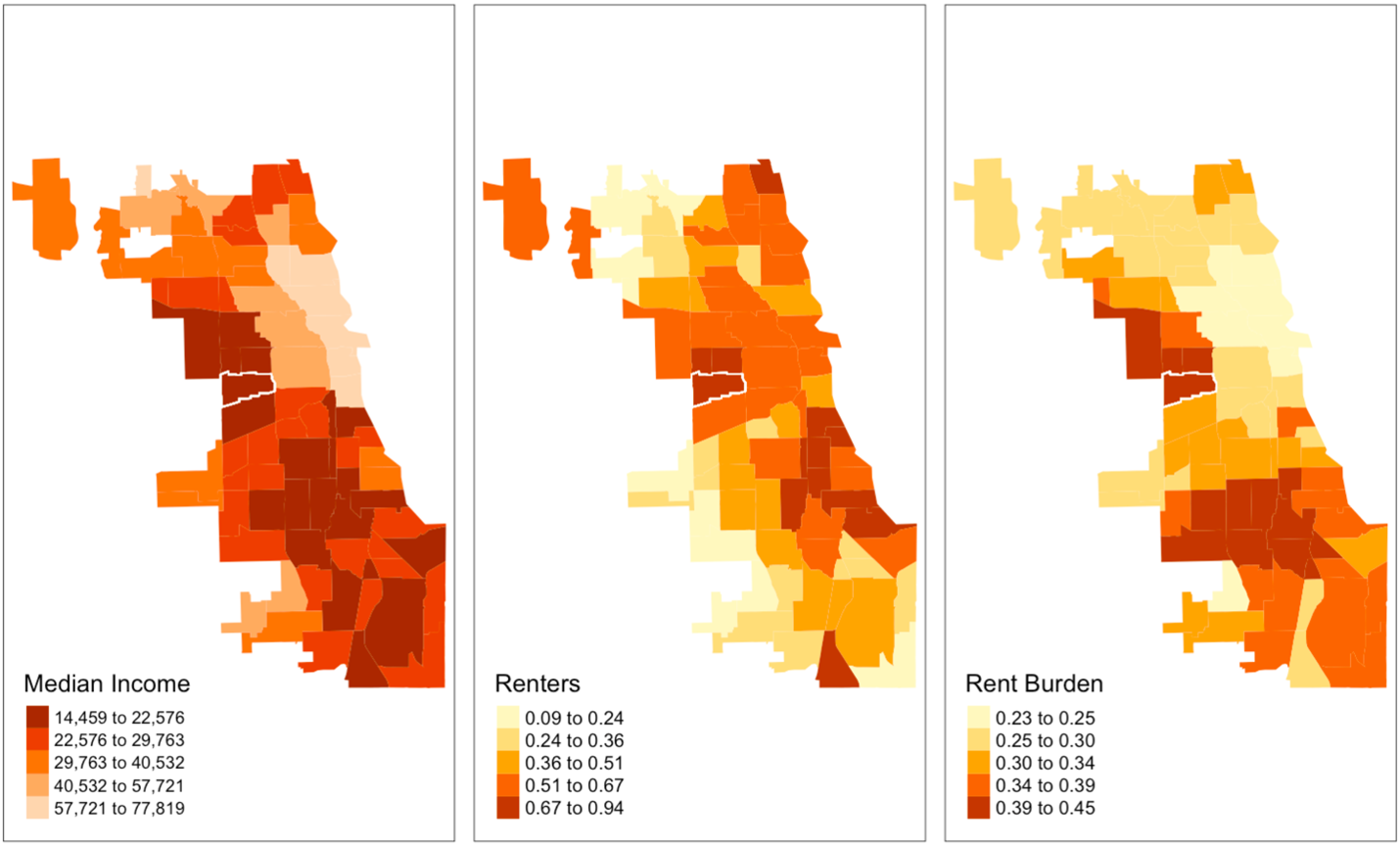

Still, we might ask why the development was not placed further west along the Ogden commercial corridor, still close to the busy Central Park Avenue bus route, but closer to the Pulaski road bus route, seen in dark red passing through North Lawndale in figure 3. One reason this decision might have been made is the fact that incomes are slightly higher in the southeast end of the community, though as we saw in figure 2, more of the lowest earning workers and more residents who we have learned are concentrated in the western tracts of the community, would be served by this alternative placement.

More fundamentally, while making use of an existing commercial corridor is difficult to argue against, we can ask why sites in the northern portion of the community were not chosen, where the lowest incomes seem to congeal and where most residents live. As I have pointed out, the chosen site appeals to both rail users and bus users within the community, but also implicitly aims to make it a destination for the entire city, possibly placing upward pressure on rents where rents and incomes are already highest in the community.

Additionally, the placement of mixed-use development alone will not determine how well it will serve residents. We can ask if bus users will be welcome in the development, if they will be free to make use of public space like visitors from other communities will, and how higher-income North Lawndale residents will. Scholars such as Kafui Attoh (2019) have noted that bus users end are often marginal to city plans, often being relocated to the margins of activity centers. Although bus is well served in this context, we can ask if bus infrastructure will be invested in and well-integrated, or simply proximal to Lawndale Redefined and socially removed from the city and developers’ vision of revitalization. Data on who occupies affordable housing is difficult to find, but Affordable Requirement Ordinance (ARO) guidelines aimed at moderate-low incomes (CMAP, 2020) and statement from previous DOH commissioner Jack Markowski saying that the affordable housing program was never meant for the poorest community members (Carranza, 2008, p.19) call into question whether affordable housing will be affordable for most existing residents or if it will attract new, wealthier residents from outside neighborhoods.

As of now, plan materials show no sign of the transportation investments promised by the initiative, let alone any signs of bus investments. The question is not whether the city and developers have intended for the space to be accessible, but if they have invested in making it accessible and if other actors such as police, retail occupants, private security, and residents (existing and new) will welcome them into the space and if they will be given the opportunity to be a part of the community making process.

Environmental Justice

More serious critiques can be made with respect to the less publicized industrial site planned for the northwest corner of the neighborhood, where population, especially lower-income populations are densest (Figure 4). With this fact in mind, it is productive to think about North Lawndale within the context of the southwest side where air quality and environmental racism have been the subject of community organizing for several decades (Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, 2021).

As local environmental justice organizations have noted, such plans fail to take into account existing air quality issues and add to traffic through the addition of semi-truck traffic (Wadell & Singh, 2021), consequential not only for drivers but for buses as they lack protected lanes and signal priority. Little Village residents in South Lawndale have been fighting against poorly executed and rushed redevelopment of industrial sites that have carpeted the area in pollutants, pushing redevelopers to work with the community on a ‘just transition’ (LVEJO, 2021). In the context of South Lawndale, this has meant pushing for not a scrapping of the projects, but pushing for projects that aim to create community self-sufficiency through food production and electrified vehicles to minimize diesel emissions (LVEJO, 2021).

While North Lawndale’s industrial use is less intense compared to South Lawndale, sneaking in more industrial use through a public investment, revitalizing an industrial corridor rather than transitioning away from diesel emitting industries, adds health burdens atop existing financial burdens. Together with other planned distribution centers, this plan threatens to inundate the southwest side with diesel emission and slower commute if not accompanied by appropriate legislations like the electrification of semi-truck fleets (LVEJO, 2021).

Final Remarks

For the sake of focus, I have not reconciled possible contradictions and fundamental limitations in the data I have relied on in this analysis; for example, the limitations of the American Community Survey which leaves out adolescents and non-work travel, missing a source of great richness as we expand the argument for high quality housing-transportation integration for reasons beyond work. I have also relied on low-resolution bus data, a source of data which could help point to possible locations for targeted investment like bus shelters and transit data monitors. Furthermore, the recent COVID-19 pandemic presents new contexts under which we can examine the relationship between race, class, and transit ridership to make an even stronger case for treating both as essential services.

I have highlighted some of contradictions and political conflicts at the heart of Invest South/West and other public investment initiatives like it, mainly the issue of internal heterogeneity and the question of whether the lowest-income residents are actively being invited to be a part the community revitalization process, proxied by how bus transit fits into the plan. Additionally, I have questioned whether a public investment program that seeks to correct historical disinvestment ought to be facilitating and catalyzing the investment of public and private money into polluting land uses, part of a larger trend of distribution centers popping up in low-income, non-white areas in Chicago and across the United States (Waddell & Singh, 2021).

This analysis represents an initial exploration of the complex conversation that residents are having in community meetings and will continue to have in meetings and in everyday life as the effects of the initial phase and future phases materialize with unknown consequence and possibilities. The success of the program, its ability to retain and improve the lives of community members, will depend on the continued negotiation of what progress looks like, what risks can be tolerated, and who is considered central to North Lawndale’s future.

References

American Public Transportation Association. (2017). Who Rides Public Transportation: Passenger Demographic & Travel [Report].

Attoh, K. A. (2019). Rights in transit: Public transportation and the right to the city in California’s

East Bay. University of Georgia Press. Athens, GA.

Carranza, M. (2008). Legislating affordable housing in Chicago’s private real estate market. Public

Interest Law Reporter, 13(1), 16-24.

Chicago Historical Society. (2005). North Lawndale. Encyclopedia of Chicago. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/901.html

Chicago Metropolitan Planning Council. (2020). Part 2: Who is benefiting from the Affordable Requirements Ordinance?. Metropolitan Planning Council. Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https://www.metroplanning.org/news/8824/Part-2-Who-is-benefiting-from-the-Affordable-Requirements-Ordinance

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. (2021). North Lawndale: Community Data Snapshot

August 2021 Release. Retrieve from https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/126764/North+Lawndale.pdf

City of Chicago. (2021). Invest South/West: About. Chicago.gov. https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/sites/invest_sw/home/about.html

City of Chicago. (2021b). CTA – Ridership – ‘L’ Station Entries – Daily Totals [Dataset]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Transportation/CTA-Ridership-L-Station-Entries-Daily-Totals/5neh-572f

City of Chicago. (2021c). CTA – Ridership – Bus Routes – Daily Total by Route [Dataset]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Transportation/CTA-Ridership-Bus-Routes-Daily-Totals-by-Route/jyb9-n7fm

City of Chicago. (2020). CTA – Bus Routes – Shapefile [Shapefile]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Transportation/CTA-Bus-Routes-Shapefile/d5bx-dr8z

City of Chicago. (2018a). CTA – ‘L’ (Rail) Stations – Shapefile [Shapefile]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Transportation/CTA-L-Rail-Stations-Shapefile/vmyy-m9qj

City of Chicago. (2018b). Boundaries – Census Tracts – 2010 [Shapefile]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Facilities-Geographic-Boundaries/Boundaries-Census-Tracts-2010/5jrd-6zik

City of Chicago. (2018c). Boundaries – Community Areas (current) [Shapefile]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Facilities-Geographic-Boundaries/Boundaries-Community-Areas-current-/cauq-8yn6

City of Chicago. (2016). Boundaries – Zoning Districts (current) [Shapefile]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Community-Economic-Development/Boundaries-Zoning-Districts-current-/7cve-jgbp

City of Chicago. (2015). CTA – ‘L’ (Rail) Lines – Shapefile. [shapefile]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Transportation/CTA-L-Rail-Lines-Shapefile/53r7-y88m

City of Chicago Department of Planning and Development. (2021a, February 24). Roosevelt & Kostner RFP Community Presentations This slideshow could not be started. Try refreshing the page or viewing it in another browser.